Pressing perils: Pakistani journalists navigate challenges reporting on religious minorities

In the Urdu version of this report, it is claimed that 45% of journalists receive threats to report news related to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Lahore-based Saleem Iqbal is an advocate for human rights and a freelance journalist. He has been in journalism for the past 25 years, primarily focusing on issues concerning the Christian community. Saleem reveals that in 2011, he reported on a case involving a Christian girl’s forced conversion and forced marriage. The authorities promptly took notice of this news, leading to the girl’s recovery and the perpetrator’s arrest.

He says that after some time, the perpetrator attacked his home. Fortunately, their family remained unharmed. After this incident, he relocated his family abroad for safety. Saleem Iqbal mentioned that many of his relatives were already residing abroad and were content there. Therefore, sending his wife and children abroad was not a major challenge for him.

In Pakistan, journalists not only face challenges related to reporting on sensitive institutions and courts but also encounter difficulties when bringing issues of the non-Muslim community to light.

The Pakistani media, especially television channels and most Urdu newspapers, often neglect news about injustices with minorities. News editors argue that such stories are suppressed to prevent exacerbating the situation further.

Saleem says he has received several threatening calls regarding his reporting on minorities. He says he even registered a First Information Report (FIR) regarding one incident, but the culprit has not been apprehended even after a year.

While reporting the Asia Bibi case, another senior journalist, Wadood Mushtaq, received threats over the phone. Subsequently, his car was fired upon. However, he remained safe. But following this incident, he and his family relocated to the UK.

Wadood states that he does not want to discuss who attacked him.

Siddra Dar, a female journalist from Karachi, is associated with Voice of America. She explains that in 2020, she reported on the case of a minor non-Muslim girl named Arzoo Rajah, who was forcibly converted and married.

She mentions that one day after meeting with Arzoo Rajah in court, she was heading home when she received a call from an unknown person.

“The caller threatened me to back off from this case. They knew where I lived when I went to the office and when I left.”

According to Siddra, she informed a few colleagues about the threatening phone call but did not take any legal action. She did not receive any further calls from the unknown number.

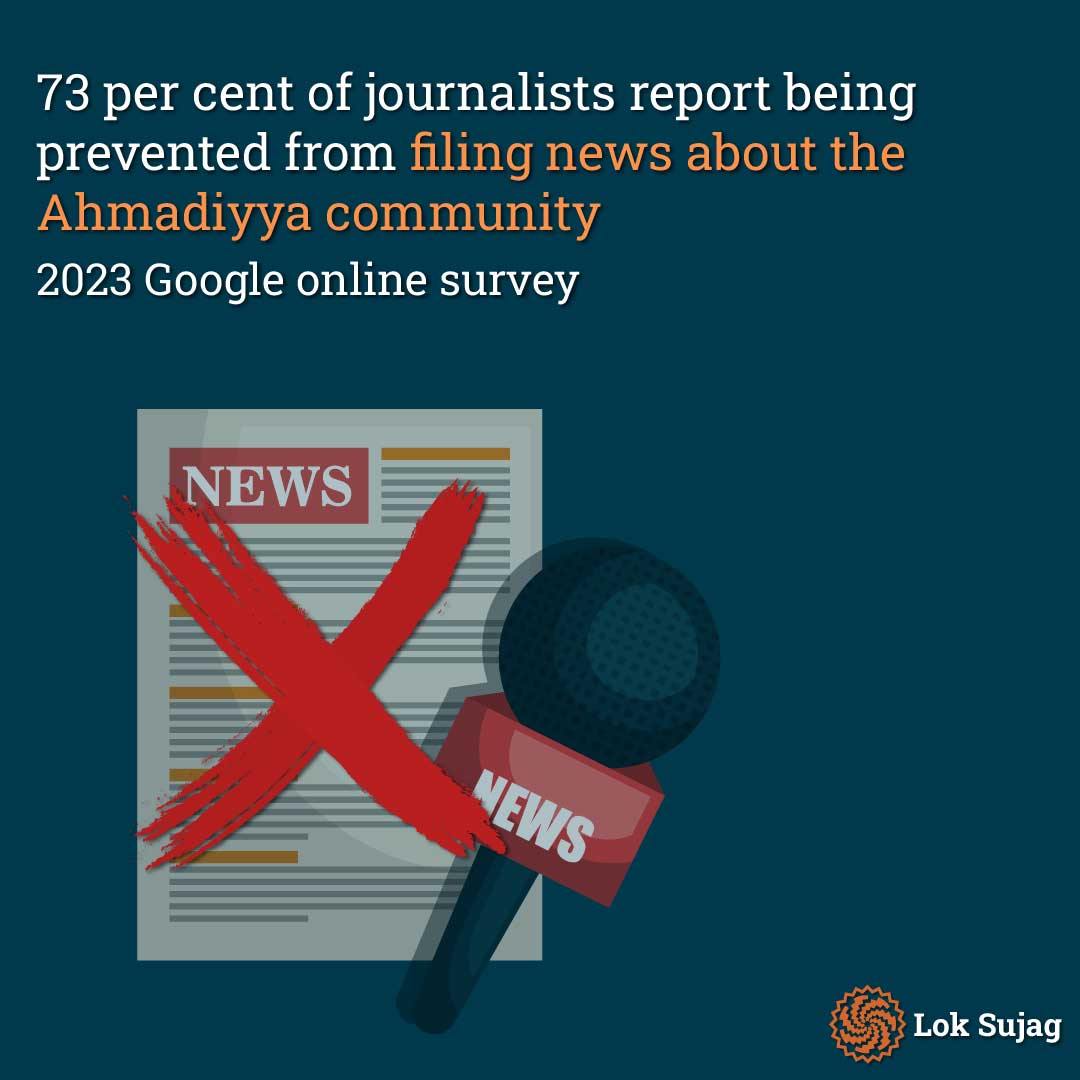

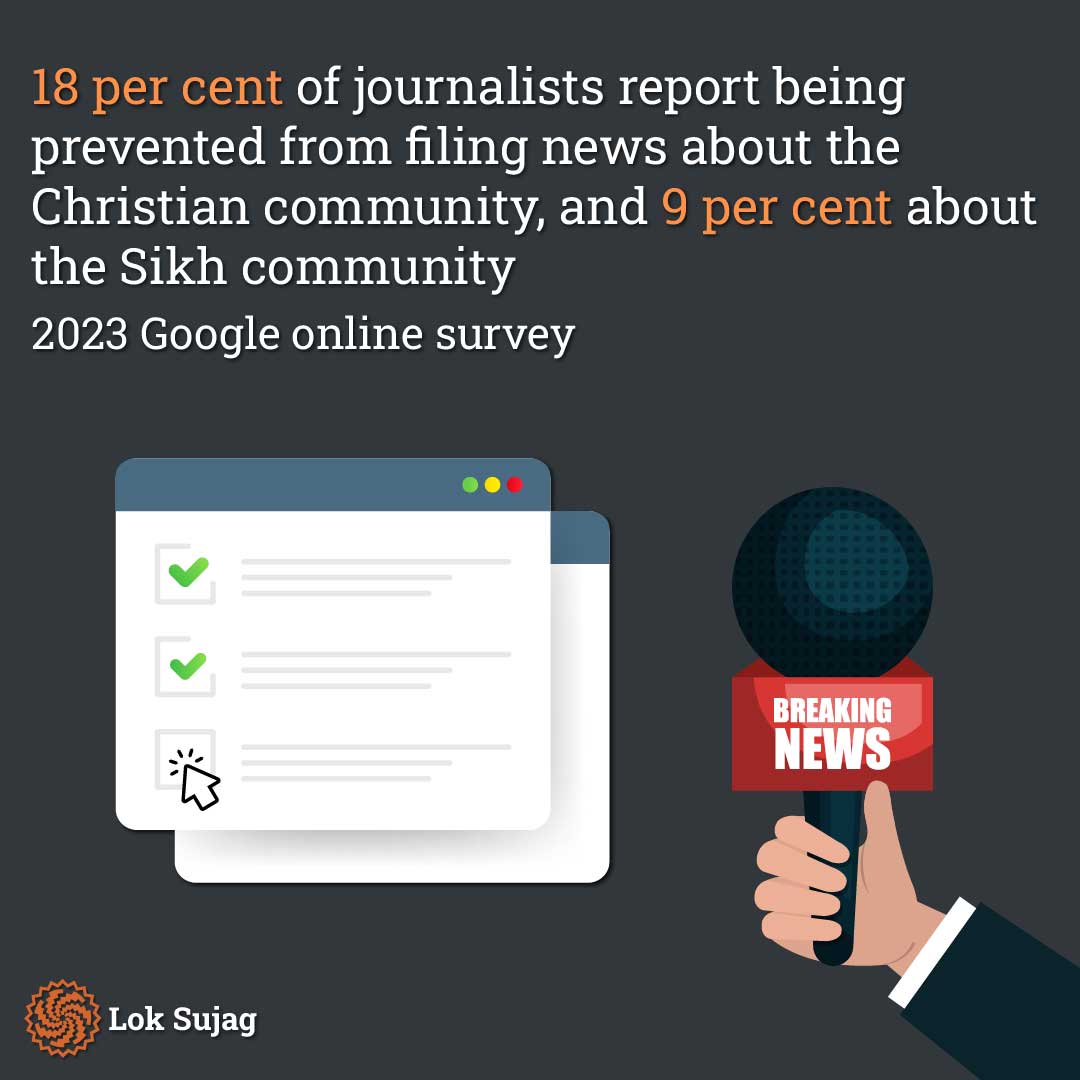

In January 2023, an attempt was made to gather opinions from journalists across the country through Google Survey Form. Journalists associated with electronic, print, and social media reported that they cannot easily cover issues related to the non-Muslim community and events.

According to 73 per cent of the journalists, they are prohibited from filing news related to the Ahmadi community. Even if a news file is submitted, it is not published. As for 18 per cent of the journalists, they are prevented from filing news about the Christian community, and according to 9 per cent, news related to the Sikh community is restricted.

On the condition of anonymity, a senior journalist from Lahore says that in 2013, when the Joseph Colony incident occurred, he was among the first journalists to arrive. He says that he sent the footage to their office and informed the newsroom about the situation.

However, the newsroom responded that the situation could become volatile, so they should take DSNG (Digital Satellite News Gathering) equipment and get back to the office. While they were on their way back, the Director News called and directed them to go back to Joseph Colony.

“I was told to keep the DSNG at a safe distance. They also told me that I might face some resistance, but instead of referring to it as a religious issue, I should use words that convey that there’s a conflict among local people.”

During the recent incident in Jaranwala, TV channel representative Rao Abdul Rahman says that he promptly transmitted news, clips, and videos from the scene to his office as protesters assembled in the morning. But he was informed that that news couldn’t be aired.

He says the government took notice by noon when everything had turned chaotic. Afterwards, news started airing on other TV channels as well. If the TV channel had addressed this issue in the morning itself, perhaps the extent of the damage wouldn’t have been as significant.

Rana Azim, the Secretary-General of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), states that now, in Pakistan, the question should be asked about how many journalists remain who have not been harassed.

He says that the duty of a journalist goes beyond religion and beliefs; it involves bringing the truth to light.

“Journalists face challenges in reporting on minority issues. Sometimes government institutions create obstacles, and at other times, media houses impose censorship under self-made policies.”

Arshad Ansari, Secretary-General of the PFUJ (Afzal Butt Group), clarifies that although preventing information on social media is now almost impossible, the national media refrains from disseminating news related to intense religious matters to avoid incitement.

In the past few years, how many journalists have been harassed or attacked by religious groups? When Punjab Police was asked for this information, no data could be obtained.

Police officials stated that they do not compile data according to categories. However, several cases have been registered over the past two years, including cases involving alleged journalist claimants. The journalist organisation PFUJ also lacks data on how many claimants were journalists.

The spokesperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan states that harassing media workers is condemnable. Such an environment affects both press freedom and interfaith harmony efforts, impacting both sides. Journalists and media workers should stand united against such actions.

Original post can be read HERE.