(ANALYSIS) In February, the Pakistan Telecommunication Agency blocked online access to Wikipedia in all of Pakistan for “sacrilegious content.” A few days later, officials reversed the decision, claiming that the benefits of Wikipedia outweighed the benefit caused by banning it entirely in order to restrict only a number of pages.

The PTA never stated which Wikipedia entries or pages contained the blasphemous content. However, in December 2020, the PTA had issued a notice to Wikipedia for “sacrilegious content,” particularly content that referred to Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the current leader of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, as a Muslim.

Since 2008, the PTA has repeatedly banned or taken steps to ban online Ahmadi content inside Pakistan. However, the PTA has now extended its efforts to block or remove content that is hosted outside of Pakistan in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Singapore and Switzerland.

Amjad Mahmood Khan, spokesperson for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, believes that PTA’s attempts to block content outside of Pakistan are alarming.

“(The PTA is attempting) to export its discriminatory blasphemy laws against foreign citizens, which include U.S. citizens, and citizens from many other countries,” he said. “If this is left unchecked, then it could create a situation where Pakistan … will continue to seek to prosecute individuals like Ahmadi Muslims living abroad. The exportation of what is effectively a global blasphemy effort is disturbing.”

Ahmadi Muslims, or collectively the Ahmadiyya, comprise a sect of Islam founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in 1889. Ahmad claimed to be the Messiah, or Mahdi, whom the Prophet Muhammad prophesied would revive, reform and peacefully restore Islam.

According to the Muslim doctrine of “khatuman-nabiyeen,” or Seal of the Prophets, the majority of Muslims believe that the Prophet Muhammad was the final prophet. Because Ahmadis believe that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad himself was a subordinate prophet to Prophet Muhammad, other Muslims view Ahmadi beliefs as blasphemous. For their part, Ahmadis contend they believe that Prophet Muhammad was the Seal of the Prophets.

As a result, Ahmadis are persecuted by other Muslims around the world, but particularly in Pakistan. The Pakistani Islamist group Khatme-Nubbawat’s main goal is to promulgate the absolute finality of the Prophet Muhammad, which directly conflicts with the Ahmadi belief that its founder was a subordinate prophet. According to Khan, Pakistan is the only nation to define who is a Muslim at the constitutional level. Even to apply for a passport as a Muslim requires one to affirm that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is a false prophet.

On Dec. 24, 2020, the PTA issued a legal notice against U.S. citizens Amjad Khan and Harris Zafar regarding trueislam.com, the U.S. Ahmadiyya community’s website hosted in the U.S. The notice stated that because Ahmadis are not allowed to represent themselves as Muslims or to disseminate their beliefs under Pakistan’s constitution, the PTA could demand the removal or blocking of the website under Pakistan’s 2016 Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act.

The notice stated that failing to abide by the PTA’s directive could result in a fine of 500 million Pakistani rupees, or $3.1 million USD, according to the exchange rate at that time.

Later correspondence from the PTA clarified that it was banning the website within the jurisdiction of Pakistan only. However, Section 1(4) of the Electronic Crimes Act, cited in the same correspondence, states that it regulates “any act committed outside Pakistan by any person if the act constitutes an offence under the Act and affects a person, property, information system or data located in Pakistan.”

According to attorney Monsura Sirajee of O’Melveny & Myers LLP, representing trueislam.com, “our repeated requests to the PTA to confirm that it is not seeking a remedy beyond geofencing the website in Pakistan (not only including a complete takedown but also criminal liability and hefty civil sanctions) have gone unanswered.” She explained that the criminal charges could result in imprisonment up to 10 years.

Sirajee said that on Dec. 30, 2020, a chief justice of the Lahore High Court issued arrest warrants for anyone outside of Pakistan who publishes online content that is deemed blasphemous. She pointed out that Section 298-B of the Pakistan Penal Code criminalizes identifying oneself as an Ahmadi Muslim.

On Dec. 25, 2020, the PTA issued a press release, the same one regarding Wikipedia content, reporting it had directed Google to remove “misleading search results associated with the ‘Present Khalifa of Islam’” as well as remove a Quran app published on the Google Play Store by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community within Pakistan.

The community had first published a Quran app on the Play Store years prior. Google notified it of a request from the PTA to remove it in September 2018. While Khan says that Google had at first left the app available upon the community’s request, Google removed it without warning in October 2019 from Pakistan’s Play Store.

In May 2020, the community released a second Quran app, to which the December. 25, 2020, notice referred. Google complied again with the PTA’s request to remove the app on Dec. 27, 2020.

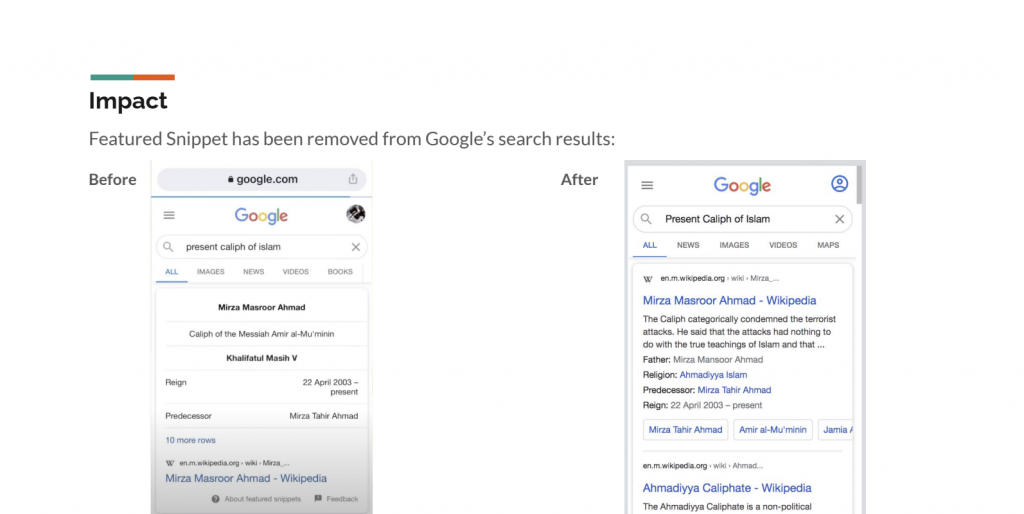

While the removal of both apps only affected Pakistan’s Play Store, Khan says that Google’s search results previously would generate a featured snippet that would list Mirza Masroor Ahmad as the current caliph of Islam when searching for the “the present caliph of Islam.” It appears that Google acquiesced to the PTA by removing the snippet also, and not just for Pakistan but on a greater transnational scale according to screenshots provided by Khan that were taken of the search results in the U.S.

On Dec. 30, 2020, according to an article in Dawn, a Lahore High Court chief justice inquired about what action Pakistan’s Federal Investigative Agency could take against someone outside Pakistan spreading blasphemous content, including registering a case against Google.

Additionally in December 2020, the PTA sent notices to the web distributor for Ahmadi websites alhakam.org, alfazl.com, alfazlonline.org, mta.tv and pressahmadiyya.com, all hosted in the U.K.

One of those notices, sent in an email dated Dec. 27, 2020, from a PTA employee, stated that because the content was hosted outside the country, “they are available throughout the country beside blocking restrictions imposed by PTA.” It instructed the owners to “take immediate necessary measures so that these are not served in the country.”

Ultimately, the PTA stated it had removed access to trueislam.com within Pakistan in a Jan. 22, 2021, press release.

Throughout 2021, the PTA continued to send notices to 24 additional Ahmadiyya websites, including trueislam.co.uk, ameauk.org, ahmadiyya.uk, lajna.org.uk, khuddam.org.uk, makhzan.org, amjinternational.org, alshirakat.org, islamahmadiyya.net, whyahmadi.org and lifeofmuhammad.org.uk in the U.K.; trueislam.com.au in Australia; khuddam.ca and jamiaahmadiyya.ca in Canada; trueislam.com.au in Australia; ahmadiyya.org.se in Singapore; aAhmadiyya.ch in Switzerland and ahmadiyyagallery.org and mkausa.org in the U.S.

All of those websites were eventually blocked by the PTA within Pakistan.

As recently as June 2022, the PTA decided to block the website ansarusa.com in Pakistan.

According to Khan, unlike Google and Apple, which have acquiesced to the PTA’s requests, Twitter and Wikimedia, the parent company of Wikipedia, have not removed Ahmadiyya content. He said that Twitter sent notices informing Ahmadiyya-related account owners that requests have been made to remove their content but has not taken the requested actions as far as he knows.

Likewise, Wikimedia has continued to host Ahmadi content.

But for Harris Zafar, national spokesperson for Ahmadiyya Press USA, tech companies’ compliance is only worsening the persecution against Ahmadis. “Big tech companies have actually fanned the flames of persecution by acquiescing to Pakistan’s demands,” he said.

Khan understands that tech companies do not want to lose access to countries with millions of users over so-called “domestic issues.” However, he says that “if you truly are benefiting from free speech, and making so much money off of robust proliferation of speech, why would you selectively restrict it when it comes to the free speech of communities that are being targeted by the government? … By doing so, tech companies are unfortunately complicit in their repression.”

He points out that virulent videos calling for the killing of Ahmadis remain on YouTube while videos of peace-loving Ahmadis are removed because they are “offensive.”

“The people who should be protected are the people who are being persecuted,” Khan said.

But Khan says that Pakistan attempting to define who is or is not a Muslim is “the single greatest threat to a unified Muslim community. No Muslim has the right to define the inner convictions … of someone’s heart.”

While any change to how other Muslims view Ahmadis will take a generational shift and acknowledgement of Ahmadis as Muslims from a constitutional approach, Khan says, “We will continue to courageously fight against religious repression wherever it is, to whoever it is, because our faith commands it. Islam stands for religious freedom for all.”

Original post can be read HERE.